Education Programs Conceptual Framework

- The Vision and Mission of Institution and Unit

- The College of Education Philosophy, Purpose, and Goals

- Knowledge Bases That Inform the Unit's Conceptual Framework

- References

The Vision and Mission of the Institution and Unit

Vision Statement – Wilmington University

Wilmington University will distinguish itself as an open-access educational institution by building exemplary and innovative academic programs and student-centered services while anticipating the career and personal needs of those it serves.

Mission Statement – Wilmington University

Wilmington University is committed to excellence in teaching, relevancy of the curriculum, and individual attention to students. As an institution with admissions policies that provide access for all, it offers opportunity for higher education to students of varying ages, interests, and aspirations.

The university provides a range of exemplary career-oriented undergraduate and graduate degree programs for a growing and diverse student population. It delivers these programs at locations and times convenient to students and at an affordable price. A highly qualified full-time faculty works closely with part-time faculty drawn from the workplace to ensure that the college’s programs prepare students to begin or continue their careers, improve their competitiveness in the job market, and engage in lifelong learning.

Mission Statement – College of Education

The College of Education at Wilmington University prepares professional educators to work successfully with children from birth through adolescence. Our programs prepare candidates to work with students with a wide variety of learning needs and diverse cultural, socioeconomic and linguistic backgrounds. An important goal of our programs is the translation of theory into practice. All programs are standards-driven. All programs emphasize the importance of data-based decision making, practical experiences in classrooms and schools, content knowledge, knowing and understanding learner needs, and the application of research-based best practices.

Vision Statement – College of Education

We believe that effective professional educators must also be learners—learners who want to share challenging ideas and successful practices with their colleagues. Educators prepared at Wilmington University believe in the importance of reflecting on and improving the quality of their work. They are committed to collaborating with parents, colleagues, and community stakeholders. They want to create teaching/learning environments that support personal development, stimulate intellectual growth and high levels of achievement, and encourage creativity. We try to maintain a climate of high expectations, hard work, caring, and respect for the worth of every individual. We view ourselves as “Professional Partners, Creating Environments for Learning.”

The College of Education Philosophy,

Purposes, and Goals

Defining Property: School Context / Philosophy

The philosophy and purposes of the degree programs in the Wilmington University College of Education flow out of the visions and missions of both the University and the College. The framework for the degree programs in the College of Education integrates several features of a program model originally proposed by the Research and Development Center for Teacher Education at the University of Texas at Austin. The model was based on one of the most comprehensive studies of programs for the preparation of educational personnel ever conducted (Griffin, et al., 1984). The model proposed that a defining property of effective programs should be relations with a school context, i.e. programs must stress practical experiences in living programs and schools. This framework is particularly suited to the mission of Wilmington University, which emphasizes “career-oriented” programs offered through faculty members with close ties to the work place and to practice, and to the mission of the College of Education, which has, as its primary purpose, “the translation of theory into practice.”

This approach does not divorce theory from practice (the “ivory tower” perspective of the college as opposed to the “real life” perspective of schools). We agree with the proposition that “theory without practice is futile and practice without theory is fatal.” Instead, our approach offers a more comprehensive view, that of providing essential theoretical foundations applied in such a way that practice will be better understood and subject to change and improvement.

This view acknowledges that the person learns from the context, but also gives attention to learning and acting beyond mere accommodation to the context. The educator-context relationship is seen as a means by which the student learns about, from, in and how to act upon the context. Rather than learning instructional methodologies in isolation, and learning only how schools operate technologically, the student learns why classrooms and schools look the way they do, what conditions constrain or promote teaching and learning, how schools come to develop their often very special characters, how to apply inquiry and analysis in the school setting, and, importantly, how to act upon school and classroom contexts for the purpose of improvement (Hoffman and Edwards, 1986, 8-9).

Our belief in the centrality of context dictates that competent teacher-practitioners be directly and broadly involved in the design and delivery of college course content. Our adjunct faculty members, who have extensive prior and current field experience, bring students face to face with the realities and challenges of today’s school culture. Theory is translated into best practices, not by theorists, but by the people who know how to do it and who actually do it everyday with real people in authentic educational settings. Their work, enhanced by collaboration with a core of full-time faculty members who have extensive teaching and school leadership experience, constitutes the backbone of our programs.

Program Purposes

As clearly specified in our mission and philosophy, a primary purpose of our professional educator preparation programs is “translating theory into practice.” Each program, including each program designed to prepare educators for licensure/certification, has a stated purpose that functions within the context of this purpose (stated above) and that enables the programs to enliven the philosophy to carry out the missions of the University and the College of Education. The stated purposes of each of the licensure/certification programs (Wilmington University Catalog) in the College are as follows:

Wilmington University Academic Catalogs

Bachelor of Science in Elementary Education:

The purpose of the Bachelor of Science degree in Education is to prepare students for teaching positions in schools serving children from birth through grade 8. Students choose a teaching concentration that leads to certification in Early Care and Education (Birth through Grade 2), Elementary Education (Grades K-6), or Middle Level Education (Grades 6-8).

Master of Education Degree in Elementary Studies:

The Elementary Studies program prepares teachers to meet the academic and social needs of students. The program is built on a model of the teacher as learner, researcher, and facilitator of knowledge. The program is based on the premises that teachers must be sensitive to varying social demands and expectations; must be able to diagnose and address the individual learning and developmental needs of students, including emotional, physical, social, and cognitive needs; must be able to use technology in all aspects of their profession; must make important decisions about how and what to teach in the face of an overwhelming knowledge explosion; and must reach out more effectively to parents and the community.

Master of Education in School Leadership:

The Master of Education in School Leadership addresses the research, theory, and practice related to effective schools, teaching and learning, and school reform. Translating theory into practice is a primary emphasis. This 33-35 credit program is designed to (a) develop aspiring school leaders’ knowledge, dispositions, and skills related to effective and sustainable school and school system leadership and renewal; (b) prepare school leaders who are committed to the centrality of teaching and learning and to the removal of barriers to student learning; (c) prepare school leaders who will engage all school stakeholders in the development of a shared vision of teaching and learning; (d) prepare school leaders who will manage school operations and resources in an efficient, equitable, and ethical manner, maintaining a constant focus on the improvement of student learning; and (e) prepare school leaders who are committed to professional growth and renewal.

Master of Education in School Counseling:

The Master of Education program in School Elementary and Secondary Counseling addresses the needs of diverse school populations facing rapid social, economic, and technical changes. Practical application in the counseling field is balanced by detailed consideration of the philosophy, theory, knowledge, and ethics necessary for a professional school counselor. All aspects of the program are directed toward enabling the participants to acquire the knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed to become effective school counselors in a developmental and multicultural school setting.

Master of Education in ESOL Literacy:

The Master of Education degree in ESOL Literacy is built around the five domains of the TESOL standards: Language, culture, Managing and implementing Standards-based ESL and Content instruction, assessment, and Professionalism. The program offers classroom teachers an opportunity to increase knowledge, skills, and techniques in all aspects of reading and writing instruction, especially relative to the needs of ESOL students. The course content is focused at the classroom level to better enable teachers to meet diverse literacy needs of students at the elementary, middle/secondary school level. The program addresses the most current theories and practices for developing strategies and techniques for teaching reading and writing, effective schools research, and educational reform and technology relative to second language acquisition. Course content includes literacy theories for second language acquisition, research results, current strategies and techniques and materials, but always focuses on the centrality of teaching and learning as it relates to the student whose first language is not English. Additional courses include a foundational reading course. As our population becomes more richly diverse, we recognize the constant need for teachers who understand the variables which affect their environments and who possess the professional skills necessary to contribute to the development, implementation, and evaluation of programs and procedures to effect increased learning, demonstration of desired outcomes, and provide sensitivity, and acceptance of cultural and linguistic diversity within school environments.

Master of Education in Elementary Special Education:

Students with special needs must be taught by professionals who are trained in the identification, assessment, and teaching of individuals with exceptionalities. To reach this goal, the Master of Education in Special Education program has three distinct options which allow the master’s candidate to focus on his/her individual needs and career goals. This program reflects an inclusion model of special education service delivery.

Master of Arts in Secondary Teaching: Grades 7-12:

The Master of Arts in Secondary Teaching program prepares teachers to meet the academic and social needs of students. The program is built on a model of the teacher as learner, researcher, and facilitator of knowledge. The program is based on the premises that teachers must be sensitive to varying social demands and expectations; must be able to diagnose and address the individual learning and developmental needs of students, including emotional, physical, social, and cognitive needs; must be able to use technology in all aspects of their profession; must make important decisions about how and what to teach in the face of an overwhelming knowledge explosion; and must reach out more effectively to parents and the community.

Doctor of Education in Innovation and Leadership:

The doctoral program facilitates the professional development of teachers, specialists, administrators, and other personnel committed to the concept that those responsible for the nation’s educational agenda must be innovative leaders. The program prepares students to translate research into effective systems of instruction, supervision, and leadership. It features a core of studies and a dissertation. This program of studies meets the needs of public, private, and post-secondary educators. The program format allows for completion of coursework in just over three years, even though students attend classes only once a week. Some of the courses may be taught in a “hybrid” format which includes both face-to-face and on-line instruction. Courses are taught by both full-time and adjunct faculty who are experts in their fields, providing an insight into innovative, leading edge theories and practices.

Program Goals

The specific, long-term goals (desired outcomes) of the programs in the College of Education at Wilmington University are unique to each degree and to each program and are delineated as graduation and program competencies. All program competencies are standards-based; are instrumental, on a daily basis, in allowing the College to apply the philosophy to achieve the mission described above.

The College of Education (COE) also develops and monitors a set of annual goals for carrying out its mission on more of a short term basis. Examples of College-wide annual goals for the 2010-2013 academic years included the following: (1) prepare all required NCATE/SPA/STATE reports for submission consistent with accreditation reporting requirements; (2) revise advisory committees to include more community stakeholders and at least one current student; (3) continue to increase % of distance and hybrid format courses; (4) increase the percentage of College of Education faculty (full-time and adjunct) who are Bb-trained and HOT-certified; (5) convert the COE Curriculum Lab to a Learning Lab/Demonstration Classroom, with appropriate technology; (6) increase the number of minority adjuncts in all COE programs; (7) increase the number of minority students in all COE programs; (8) participate in all Wilmington University scheduled recruiting programs at all sites; (9) continue to expand resources available to students and faculty in the Learning Lab; (10) complete the NCATE Electronic Exhibit Room; (11) prepare for and complete a successful NCATE accreditation visit. In addition to the College-wide goals, the educator preparation programs set and monitor annual goals as well.

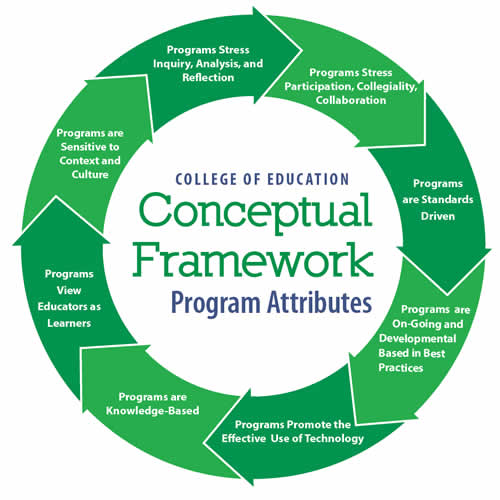

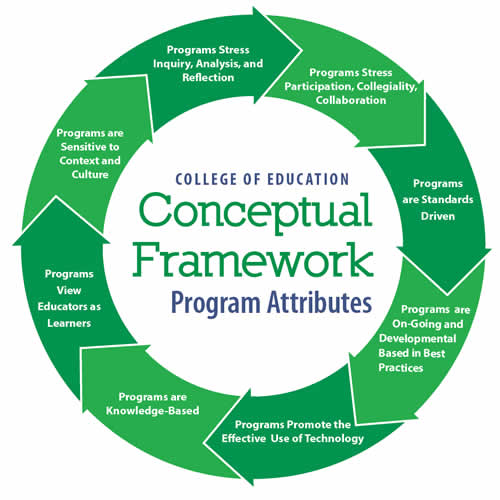

The core of our Conceptual Framework (below) emanates from the visions and missions of the University and College; reflects the philosophy, purposes, and goals noted above; and is composed of specific program attributes that we deem essential for the effectiveness of educator preparation programs.

The Conceptual Framework/Schematic

Knowledge Bases That Inform The Unit’s

Conceptual Framework

Organizing Theme, “Professional Partners Creating Environments for Learning”

We chose to organize our programs around the combined themes of professional partnerships and learning environments. These flow out of the vision, mission, and philosophy of the University and relate well to the purposes of each of our programs. We believe this approach to be central to a context-embedded program. We believe in the concept of gemeinschaft (Tonnies, 1957; Sergiovanni, 1996), or schools as learning communities, characterized by shared vision, shared rules, shared values, shared expectations, and a shared commitment toward interpersonal caring.

We believe that successful partnerships (and communities) require shared and consensual decision-making, interactive planning/problem solving, mutual benefit (reciprocity) and shared accountability. Some have suggested that this entails “moving from symbiosis to near organic fusion” (Goodlad, 1994; Schlechty & Whitford, 1989; Schlechty & Whitford, 1986) and that it is our goal to “fuse” the process of preparing educators with the contexts in which they will eventually work.

Successful partnerships are directly related to the degree to which the partners share a sense of ownership. We subscribe to the principle that those who have shared in formulating and carrying forward programs for the preparation of educational personnel (as opposed to being only the recipient of a set of externally-imposed specifications) will feel a strong investment in the success of those programs (Hoffman and Edwards, 1986). We believe that such partnerships ultimately result in a strengthening of the practical and professional preparation of our students and a sense of increased professional dignity among all participants in our programs. Key players in the College of Education’s partnerships include our students, the college faculty and staff, practicum mentor teachers and supervisors, cooperating teachers and internship supervisors, schools and their communities, the State Department of Education, our accrediting agencies and others who are interested in school improvement and reform.

Program Attributes Which Define the Conceptual Framework

The manner in which we prepare educational personnel is informed by eight essential attributes which serve as the theoretical base for our programs and which serve as the core of our conceptual framework. These attributes include (1) ensuring the programs are knowledge-based; (2) viewing educational personnel as learners, including a focus on deconstructing past experiences as learners in coursework and field experiences and developing appropriate knowledge of the content and discourse of the disciplines to be taught; (3) promoting contextual and cultural sensitivity; (4) enabling authentic participation, collegiality, and collaboration; (5) facilitating inquiry, analysis and reflection, i.e., providing structured opportunities for critical reflection on and taking action on one’s daily work; (6) building an on-going, developmental program that allows for continuous improvement, experimentation, and professional growth; (7) ensuring that programs are standards-driven; and (8) ensuring that programs promote the effective use of technology. The program attributes are more fully described below.

1. Programs are Knowledge-Based

We believe that programs designed to prepare educational personnel must be knowledge-based. Educators must acquire, and keep acquiring, a broad foundation of general knowledge in the liberal arts, mathematics, and the sciences and specific knowledge in the content areas which are the focus of their work. We also believe that there is an essential body of verified and reliable knowledge about teaching and learning that educational personnel must acquire. We believe that this knowledge is more than a set of discrete facts, lists, prescriptions and findings. We believe that this knowledge includes a coherent set of facts and other information that together allow us to make judgments, come to informed decisions, suggest desirable practices, and ask important questions (Danielson, 2002; Griffin, et al., 1984; Marzano, 2003).

We believe that relying totally upon this body of knowledge is insufficient when making decisions about teaching, schooling, and the preparation of educational personnel. We believe that single-minded dependence on empirical knowledge gained from highly disciplined process-product studies leads to an excessively narrow vision. We believe that theoretical knowledge is of major importance. Theory is particularly powerful in helping educational personnel understand and make sense of their professional worlds. We believe that theory can lead thoughtful students to make their own discoveries as a consequence of increased understandings. We believe that theory can also provide a body of shared understandings across groups of educators who are trying to come to decisions about how to practice their profession (Hoffman & Edwards, 1986, p. 14).

A clear example of this theory-to-practice linkage includes our college-wide efforts to model and integrate, in all education coursework and experiences, elements of Adult Learning Theory (Knowles , 2005). Other examples include: how Activity Theory (Nardi, 1996) , Subsumption Theory (Ausubel , 1963) , and Bransford’s Theory of Anchored Instruction (Bransford, 1990) relate to problem-based and activity-oriented lesson design; how the work of Sternberg in Successful Intelligence (Sternberg, 1999) and Gardner in Multiple Intelligences (Gardner, 1985) link to developing diverse instructional strategies and assessments; and how and why Dewey’s seminal ideas about constructing meaning from experience, collaboration, inquiry, activity and creativity are even more important in today’s schools. Still other examples of theories that influence our work include how Experiential Learning Theory (Kolb, 1984 and Rogers & Freiberg, 1994) and Transformation Theory (Mezirow , 1980) helps us to understand the power and importance of reflection and the need to link learning with prior knowledge and experience; how the work of Lewin and Barker in Field Theory and Behavior Setting Theory (Barker, 1968; Lewin, 1948; and Lewin, 1951) can help educators understand person-environment interactions and create more effective and appropriate learning environments; and how the theories of Dreikurs and Glasser can help educators develop skills to manage learning and classroom discipline and discipline in the school more effectively (Dreikurs, et al. and Glasser, 1965).

A third conception of knowledge deals with how educational personnel deal with issues that are multi-dimensional, unpredictable, highly interactive, urgent, and increasingly related to societal pressures and influences (Doyle, 1977). Responses to this complexity are founded in what we can term propositional knowledge. Propositional knowledge refers to those ideas for schooling activity that are put forth as proposals and suggestions for change that have yet to be given empirical or theoretical tests of effectiveness. Such knowledge is important for its promise for making desirable changes in educational settings. We believe that propositional knowledge can be an important base for planning and implementing programs related to the preparation of educational personnel (Hoffman & Edwards, 1986, p. 15).

The fourth conception of knowledge that we believe to be essential to our programs is what the educational philosopher and researcher, Maxine Green, calls craft knowledge. Craft knowledge refers to a coherent body of knowledge that has emerged from practical situations, cumulative over time. Educational personnel discover that certain practices, certain ways of meeting and talking with students and parents, certain materials for instruction, certain techniques for improving standardized test performance, certain room arrangements, certain incentives, certain management and transition techniques , etc., “work” again and again. While this knowledge is not necessarily empirical, experienced professionals know that some stimuli for learning are more powerful than others for inducing that learning. When this understanding occurs, another piece of craft wisdom, one of those many and critical “tricks of the trade,” is accumulated. We believe that this wisdom of education, the profession’s “hidden curriculum,” is best transmitted to educational personnel through direct, collegial, reflective, frequent, context-based interactions among experienced, beginning and pre-service educators (Green, 1984).

2. Programs View Educators as Learners

We adopt a stance toward the preparation of educational personnel that requires us to assist educators in continually updating and building and rebuilding knowledge structures about teaching and learning. We believe in the importance of continual learning throughout one’s career and in the educator as a model of continual learning. This stance is a shift from the position that the primary purpose of our work is only to provide advice to beginning educators in mastering technical skills such as writing behavioral objectives and utilizing proper lesson plan formats or mastering particular instructional models separate from the context of learners’ needs. We do not endorse the “para-professionalization” of education, wherein the educator’s work is only considered a technical (rather than intellectual or substantive) activity, one that is easily taught, efficiently observed, and readily remedied (Griffin, 1985). We do endorse the concept of the educator as a life-long learner.

3. Programs are Sensitive to Context and Culture

Students at Wilmington University learn how to adjust and adapt educational methodologies in an equitable, contextually appropriate and culturally sensitive manner. The definition of what makes an educator effective has changed dramatically in recent years , and continues to change. We believe that effective educators in today’s and tomorrow’s schools must understand the relevance of both their own and their students’ skin color, cultural heritage, gender, ethnicity, social group, social class and status, religion, health, age, first language, family structure, sexual orientation, learning style, developmental level, abilities and disabilities, etc. (Banks, 2001 and Gollnick & Chinn, 1998). We believe that all educators must work for the creation of truly egalitarian school communities, must strive to affirm interdependence and diversity, must be advocates for all children and families and must make every effort to promote equal educational opportunity and social justice. We believe that all educators must have the dispositions to work effectively with children, families, and all school and community stakeholders.

4. Programs Stress Inquiry, Analysis, and Reflection

We believe that reflecting upon one’s activities is a powerful way to increase professional authority and effectiveness (Dewey, 1944; Schon, 1991). We believe, and research confirms, that reflective practice promotes (a) greater awareness of personal performance leading to improved practice, (b) increased student learning, (c) enhanced professional growth and development, (d) a more clear and honest perspective about one’s work, and (e) greater satisfaction with oneself and one’s work (York-Barr, et al., 2001, p. 13). As reflective inquirers, prospective educators bring personal, social, and theoretical knowledge to bear to promote instructional and school improvement. We encourage our students to be inquirers into all aspects of their learning and practice. This approach is emphasized in the earliest pre-service practicum experiences and continues throughout middle field experiences, methods courses, and student teaching/internships. The approach is central to all programs, including those designed to prepare instructional leaders, counselors, and specialists.

5. Programs Stress Participation, Collegiality and Collaboration

Participation, collegiality, and collaboration are essential ingredients in our conceptual framework. We believe that educational change and improvement cannot be viewed as one educator doing a better job in one learning situation. Reforming pedagogy for sustained and worthwhile change in schools is a collaborative process requiring educators to be skilled at working in collaborative work cultures and taking initiatives such as forming broadly-based focus or study groups to investigate crucial topics (Johnston, 2000; Lieberman, 1988; Bird & McIntyre, 1999; McIntyre & Byrd, 2000). We take the notions of participation, collegiality, and collaboration very seriously in individual courses and in program structure. This can be readily seen in our extensive use of practitioner-professors, our efforts to utilize a workable collaborative model for practica and other field experiences and for the clinical semester (Gray, 2002), our frequent faculty development sessions, our formal linkage of full-time faculty with adjunct faculty and our working relationships with local schools and school districts and with the community and State.

6. Programs are On-Going and Developmental Based on Best Practice

We believe that the professional life of an effective educator is a continuum, a stream of activity that begins when a person decides to begin professional and academic study leading toward a teaching career and ends only when the decision is made to end that career (Hoffman & Edwards, 1986, p. 16). We view the development of educators in three stages: pre-service education, induction, and in-service education. We promote the notion that educators grow and change, adapt and reconstruct their worlds, and accumulate and discard ideas and practices (Fuller & Brown, 1975). We believe that programs for the preparation of educational personnel should be long-term investments in the educators themselves, in instilling in all educators the understanding of best practice as related to the teaching and learning of all children, and in the advancement of society as a whole. In promoting the on-going and developmental nature of our programs, considerable progress has been made in terms of maintaining contacts with graduates, working with graduates to assist in the preparation of our students during fieldwork and clinical experiences, completing follow-up surveys to assess student satisfaction with the programs, and continually assessing the programs for further development and improvement.

7. Programs are Standards-Driven

We believe that programs for the preparation of educational personnel should be standards-driven. We support Delaware’s school reform initiatives, one part of which was the collaborative development and adoption of uniform sets of standards that can be applied to all Delaware teachers and educational leaders, the “Delaware Professional Teaching Standards,” adopted 1998 and revised in 2003 and the “Delaware Administrator Standards,” adopted 1998, and revised/adopted the ISLLC/ELCC Standards, 2002 (Delaware Department of Education, 1998; Delaware Department of Education, 1998; Delaware Department of Education, 2002; and Delaware Department of Education, 2003). We support and utilize the Delaware Student Content Standards which define what K-12 students in our state need to know and be able to do (Delaware Department of Education, 1995) and the Common Core Standards adopted by the State in 2011, including the Next Generation Science Standards. We also support similar standards as put forth in surrounding states. We integrate those standards (and relevant national standards) into all courses and field and clinical experiences and use them as the basis for assessment of each student’s progress toward meeting professional and program competencies. We also use and support the use of the CAEP standards and, where appropriate, the standards of the various specialized professional associations related to CAEP.

8. Programs Promote the Effective Use of Technology

While we don’t subscribe to the view that each new technological advance will “revolutionize” education, we do believe that the effective use of technology in the school and classroom can and should empower both educators and learners. We believe that technology can help educators and students better cope with limited personal and institutional resources. In our programs, we emphasize the use of technology as both a teaching and management tool. We believe that all students and educators in all schools must have open access to data and information via the information superhighway. We also believe that the effective use of technology can have powerful effects on the classroom environment, including changing the relationships between teachers and learners (McGrath, 1998, 58-61).

Some of those effects can be:

- Increased student motivation

- by making classroom activities seem more connected and relevant to the “real” world, often causing students to view such activities more seriously.

- by providing increased opportunities for thematic, interdisciplinary explorations that attract, engage and excite student interests.

- More opportunities for cooperation, collaboration and decision making.

- Deeper and more probing conversations between teachers and students and among students themselves.

- The emergence of the teacher-as-facilitator role.

- A more equitable “balance of power” between teacher and students.

- Increased student persistence in solving problems.

- More varied, multiple assessments of learning outcomes.

- Improved levels of equity and cultural sensitivity.

- Improved teacher effectiveness with diverse student groups.

- Improved oral and written communications.

Given these beliefs, programs for the preparation of educational personnel are designed to:

- raise educator candidates’ comfort levels with technology.

- help candidates understand the ways in which technology can increase efficiency and effectiveness.

- teach candidates how to use technology/data sources that can enhance and enrich instruction.

- help candidates learn how to integrate technology into record keeping/management functions, lesson planning, assessment of learning outcomes, and program improvement.

- provide laboratory training and field-based opportunities for authentic application of knowledge and skills.

References

The references listed immediately below guided our thinking in the development of our Conceptual Framework and now influence our work at bringing “theory into practice” through our programs in the College of Education at Wilmington University. “Additional references” listed below relate specifically to our Program Attributes, demonstrate our expanded view of those attributes, and illustrate how we bring our Conceptual Framework alive in our work with students.

Philosophy

Griffin, G., Barnes, S., Hughes, R., O’Neal, S., Defino, M., Edwards, S., and Hukill, H. (1984). Changing teacher practice: Final report of an experimental study. Austin, TX: The University of Texas at Austin, Research and Development Center for Teacher Education.

Hoffman, J., and Edwards, S. (1986). Reality and reform in clinical teacher education. New York: Random House.

Organizing Theme

Goodlad, J.I.(1994). Educational renewal: Better teachers, better schools. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Limited.

Hoffman, J., and Edwards, S. (1986). Reality and reform in clinical teacher education. New York: Random House.

Schlechty, P.C. & Whitford, B.L. (1986). Public school and teacher education reform: A proposal for shared action . New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 27, 37-47.

Schlechty, P.C. & Whitford, B.L. (1989). Systematic perspectives on beginning teacher programs. Elementary School Journal, 89 (4), 441-49

Sergiovanni, T. (1996). Leadership for the schoolhouse. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Tonnies, F. (1957). Gemeinschaft und gesellschaft [Community and Society]. (C.P. Loomis, ed. and trans.). New York: Harper Collins. (Originally published in 1887).

Program Attribute 1 - Programs are Knowledge Based

Ausubel, D. (1963). The psychology of meaningful verbal learning. New York:

Grune & Stratton.

Barker, R. (1968). Ecological psychology: Concepts and methods for studying the environment of human behavior. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Bransford, J., et al. (1990). Anchored instruction: Why we need it and how technology can help. In D. Nix & R. Sprio (Eds.). Cognition, education and multimedia. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum Associates.

Danielson, C. (2003). Enhancing student achievement: A framework for school improvement. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Doyle, Walter R. (1977). Learning in the classroom environment. Journal of Teacher Education, 28 (6), 51-55.

Dreikurs, R., Grunwald, B. & Pepper, F. (1982). Maintaining sanity in the classroom. New York: Harper and Row.

Gardner, H. (1985). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York: Basic Books.

Glasser, W. (1965). Schools without failure. New York: Harper and Row.

Green, M. (1984). How do we think about our craft? Teachers College Record, 8, No. 1.

Hoffman, J., and Edwards, S. (1986). Reality and reform in clinical teacher education. New York: Random House.

Knowles, M., Holton, E. & Swanson, R. (2005). The adult learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development. London: Butterworth-Heinneman.

Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Lewin, K. (1948). Resolving social conflicts: Selected papers on group dynamics. G. Lewin (Ed.). New York: Harper & Row.

Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social science: Selected theoretical papers. D. Cartwright (Ed.). New York: Harper & Row.

Marzano, R. (2003). What works in schools: Translating research into action. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Mezirow, J. (1980). “How critical reflection triggers transformational learning” in Fostering critical reflection in adulthood: A guide to transformative and emancipatory learning. J. Mezirow (Ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Nardi, B. (Ed.). (1996). Context and consciousness: Activity theory and human computer interaction. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Rogers, C. & Freiberg, H. (1994). Freedom to learn (3 rd Ed.). Columbus, OH: Merrill/MacMillan.

Sternberg, R. (Ed.). (1999). Handbook of creativity. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Program Attribute 2 – Programs View Educators as Learners

Griffin, G. (1985). The para-professionalization of teaching. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Center, Chicago.

Program Attribute 3 – Programs are Sensitive to Context and Culture

Banks, J.A. (2001). Cultural diversity and education: Foundations, curriculum, and teaching. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Gollnick, D.M. & Chinn, P.C. (1998). Multicultural education in a pluralistic society. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill.

Program Attribute 4 – Programs Stress Inquiry, Analysis,

and Reflection

Dewey, J. (1944). Democracy and education. Toronto: MacMillan Company.

Schön, D. (1991). The reflective turn: Case studies in and on educational practice. New York: Teachers College Press, Columbia University.

York-Barr, J., Sommers, W., Ghere, G. & Montie, J. (2001). Reflective practice to improve schools. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Program Attribute 5 – Programs Stress Participation, Collegiality, and Collaboration

Bird, D.M. & McIntyre, D.J. (1999). Research on professional development schools: Teacher education yearbook VII. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Gray, J. (2002). Changing the culture of student teaching at a small, private college. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Teachers College, Columbia University.

Johnston, M., Brosnan, P., Cramer, D., & Dowe, T. (2000). Collaborative reform and other improbable dreams: The challenge of professional development schools. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Lieberman, A. (1988). Building a professional culture in schools. New York: Teachers College Press.

McIntyre, D.J. & Bird, D.M. (2000). Research on effective models for teacher education: Teacher education yearbook VIII. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Program Attribute 6 – Programs are On-Going and Developmental Based on Best Practice

Fuller, F.F. & Brown, O. (1975). Becoming a teacher. In Kevin Ryan (Ed.), Teacher education: 74 th yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hoffman, J., and Edwards, S. (1986). Reality and reform in clinical teacher education. New York: Random House.

Program Attribute 7 – Programs are Standards-Driven

Delaware Department of Education. (1995, June). Delaware (student) content standards. Dover, DE.

Delaware Department of Education. (1998, January). Delaware professional teaching standards. Dover, DE.

Delaware Department of Education. (1998, April). Delaware administrator standards.

Dover, DE.

Delaware Department of Education. (2002, September). Delaware administrator standards. Dover, DE.

Delaware Department of Education. (2003, July). Delaware professional teaching standards. Dover, DE.

Program Attribute 8 – Programs Promote the Effective Use

of Technology

McGrath, B. (1998). Partners in learning: Twelve ways technology changes the teacher-student relationship. T.H.E. Journal, 25(9), 58-61.

Additional References Influencing Our Work In Implementing the Conceptual Framework

The additional references listed below relate specifically to the Program Attributes included in our Conceptual Framework and illustrate (1) how our knowledge base extends well beyond the sources cited above and (2) how we bring the Conceptual Framework alive in our work with students.

Program Attribute 1 – Programs are Knowledge-Based

Brooks, J. & Brooks, M. (1993). The case for constructivist classrooms. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Bruner, J. (1996). The culture of education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cromier, S. (2001). The professional counselor: A process guide for helping. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Cummings, C. (2001). Managing to teach. (3 rd Edition). Edmonds, WA: Teaching, Inc.

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think. New York: D.C. Heath.

Herlihy, B. & Corey, G. (1996). ACA ethical standards casebook. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Leithwood, K. (1992). The move toward transformational leadership. Educational Leadership, 49, 5 (February, 1992), pp. 8-12. ERIC Identifier: EJ 439 275.

Marzano, R. (2004). Building background knowledge for academic achievement. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Murphy, J. & Louis, K. (Eds.) (1999). Handbook of research on educational administration: A project of the American educational research association. Second Edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Parkay, F. & Stanford, B. (2004). Becoming a teacher. Boston: Pearson Education.

Sergiovanni, T. (1996). Leadership for the schoolhouse. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Sharf, R. (2004). Theories of psychotherapy and counseling. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Program Attribute 2 – Programs View Educators as Learners

Argyris, C. and Schön, D. (1974). Theory in practice: Increasing professional effectiveness. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Barkley, W., McCormick, W. & Taylor, R. (1987). Teachers as workshop leaders: A model for teachers training teachers. Journal of Staff Development, 8/2

(Summer, 1987), 45-48.

Bodine, R. & Crawford, D. (1998). Handbook of conflict resolution: A guide to building quality programs in schools. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Boyer, E. (1995). The basic school: a community for learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Butcher, J. (2002). Clinical personality assessment. New York: Oxford

University Press.

Cobb, N. (2004). Adolescence: Continuity, change and diversity. New York:

McGraw Hill.

Kapes, J. & Mastie, M. (1998). A counselor’s guide to career assessment instruments. Alexandria, VA: National Career Development Association.

Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Rogers, C. (1969). Freedom to learn. Columbus, OH: Merrill.

Program Attribute 3 – Programs are Sensitive to Contect and Culture

Armstrong, T. (1993). 7 kinds of smart: identifying and developing your many intelligences. New York: Penguin Books.

Baruth, L. & Manning, M. (2003). Multicultural counseling and psychotherapy: a lifespan perspective. New Jersey: Merril Prentice Hall.

Chapman, C. (1993). If the shoe fits…how to develop multiple intelligences in the classroom. Palatine, IL: IRI/Skylight Publishing, Inc.

Guild, P. & Garger, S. (1985). Marching to different drummers. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Heward, W. (2005). Exceptional children. (8 th Edition). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/MacMillan.

Huber-Brown, T. (2002). Teaching in the diverse classroom: Learner-centered activities that work. National Educational Services.

Remley, T. & Herlihy, B. (2001). Ethical, legal, and professional issues in counseling. New Jersey: Merril Prentice Hall.

Robins, K., Lindsey, R., Lindsey, D. & Terrell, R. (2002). Culturally proficient instruction: a guide for people who teach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Seifert, K. & Hoffnung, R. (2000). Child and adolescent development. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Sergiovanni, T. (2005). Strengthening the Heartbeat. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Program Attribute 4 – Programs Stress Inquiry, Analysis, and Reflection

Danielson, C. (1996). Enhancing professional practice: a framework for teaching. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Drummond, R. (2004). Appraisal procedures for counselors and helping professionals. New Jersey: Merril Prentice Hall.

Egan, G. (1996). The skilled helper: a systematic approach to effective helping. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Eisner, E. (1995). The art of educational evaluation: A personal view. London; Philadelphia: Falmer Press.

Eisner, E. (1998). The enlightened eye: Qualitative inquiry and the enhancement of educational practice. Upper Saddle, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Kerka, S. (2000). Career and technical education: A new look. (In Brief #8). Columbus, OH: National Center for Career and Technical Education, Ohio State University.

Okun, B. (2002). Effective helping: interviewing and counseling techniques. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Program Attribute 5 – Programs Stress Participation, Collegiality, and Collaboration

Brown, D., Pryzwansky, W. & Schulte, A. (2001). Psychological consultation: introduction to theory and practice. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Dinkmeyer, D. & Carlson, J. (2001). Consultation: creating school-based interventions. Ann Arbor, MI: Sheridan Books.

Gray, J. (1999, February). A collaborative model for the supervision of student teachers. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the AACTE. Washington, D.C.

Johnson, D., Johnson, R. & Holubec, E. (1994). The new circles of learning: Cooperation in the classroom and school. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Kampwirth, T. (2005). Collaborative consultation in schools. New Jersey: Merril Prentice Hall.

Kirchhoff, S. (1989, November). Collaborative university/school district approaches for student teaching supervision. Paper presented at the annual conference of the National Council of States on In-service Education. San Antonio, Texas.

Oja, S. & Ham, M. (1987, February). A collaborative approach to leadership in supervision. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the AACTE. Washington, D.C.

Sergiovanni, T. (1994). Building community in schools. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Tonnies, F. (1957). Gemeinschaft and gesellschaft [community and society]. C. Loomis, (Ed. and trans.). New York: Harper Collins (Originally published, 1887).

Program Attribute 6 – Programs are On-Going and Developmental Based on Best Practice

Armstrong, T. (1993). 7 kinds of smart: Identifying and developing your many intelligences. New York: Penguin Books.

Arter, J, & McTighe, J. (2001). Scoring rubrics in the classroom: using performance criteria for assessing and improving student achievement. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Cooper, H. & Good, T. (1983). Pygmalion grows up: studies in the expectation communication process. New York and London: Longman.

Glickman, C. (1985). Supervision of instruction: A developmental approach. Newton, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Gregory, G. & Chapman, C. (2002). Differentiated instructional strategies: one size doesn’t fit all. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Gysbers, N. & Henderson, P. (1997). Comprehensive guidance programs that work – II. ERIC/Cass Publications. New Jersey: Merril Prentice Hall.

Jensen, E. (1998). Teaching with the brain in mind. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Marzano, R. (2001). Classroom instruction that works: research-based strategies for increasing student achievement. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Marzano, R. (2003). Classroom management that works: research-based strategies for every teacher. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Popham, J. (2002). Classroom assessment: What teachers need to know. Third Edition. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Purkey, W. (1978). Inviting school success: A self-concept approach to teaching and learning. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Routman, R. (1991). Invitation: Changing as teachers and learners K-12. Portsmouth, NJ: Heinemann.

Shelton, F. & James, E. (2005). Best practices for effective secondary school counseling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Tomlinson, C. (2001). How to differentiate instruction in mixed-ability classrooms. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Wolfgang, C. (1999). Solving discipline problems: methods and models for today’s teachers. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Program Attribute 7 – Programs are Standards-Driven

Cobia, D. & Henderson, P. (2003). Handbook of school counseling.

Council of Chief State School Officers. (1996). J. Murphy and N. Shipman (Eds.). Interstate school leaders licensure consortium: Standards for school leaders.

Washington, DC.

Danielson, C. (1996). Enhancing professional practice: a framework for teaching. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Herlihy, B. & Corey, G. (1996). ACA ethical standards casebook. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Hessel, K. and Holloway, J. (2002). A framework for school leaders: Linking the ISLLC standards to practice. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service.

International Society for Technology in Education. (2004). National educational technology standards for teachers (NETS*T). Eugene, OR.

International Society for Technology in Education. (2001). Technology standards for school administrators (NETS*A). Eugene, OR.

Interstate New Teacher Assessment and Support Consortium. (1994). Draft model standards for licensing new teachers. (L. Darling-Hammond, Chair, Standards Drafting Committee). Documents provided by the Delaware Department of Public Instruction, Dover, DE.

National Board for Professional Teaching Standards. (1994, June). Draft report on standards for national board certification. Documents provided by the Delaware Department of Public Instruction, Dover, DE.

National Policy Board for Educational Administration. (2002). Standards for advanced programs in educational leadership. Arlington, VA.

Parkay, F. & Stanford, B. (2004). Becoming a teacher. Boston: Pearson Education.

Program Attribute 8 – Programs Promote the Effective

Use of Technology

Galvin, J. & Scherer, M. (1996). Evaluating, selecting, and using appropriate assistive technology. Austin, TX: Pro-ed.

Grabe, M. & Grabe, C. (2004). Integrating technology for meaningful learning. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Neukrug, E. (2004). The world of the counselor. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Niles, S. & Harris-Bowlsbey. (2005). Career development interventions in the 21 st century. New Jersey: Merril Prentice Hall.

Reiser, R. & Dempsey, J. (2002). Trends and issues in instructional design and technology. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall.

Roblyer, M. (2003). Integrating educational technology into teaching. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.